Note: If you have not read The Moviegoer, you may want to pass on reading this post. It contains extensive excerpts and exposes some key plot points.

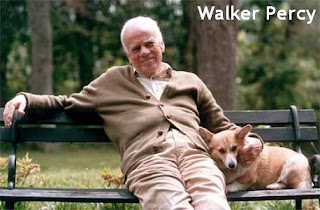

Because many of my friends from Queens University of Charlotte are Walker Percy acolytes, I was drawn—happily, it turns out—to The Moviegoer, Percy’s first novel and the winner of the 1962 National Book Award for Fiction. Published when Percy was 46 years old (an encouraging factoid for those of us in our late 40s who remain unpublished), this brilliant and penetrating novel is, more than anything else, a psychological and emotional journey. It is what I would call the South’s answer to Richard Yates’s Revolutionary Road. Percy, like Yates, gives us commonplace characters whose uncommon thoughts, feelings, and actions, both large and small, expose an America that is tidy and prosperous on the surface, but decadent, aggrieved, and desperate underneath.

Percy’s answer to Yates’s Frank Wheeler is Jack Bolling, the first-person protagonist who serves as the mirror against which post-war America is reflected. The most prominent citizen of Jack’s world, within the space of the novel, is Kate Cutrer, his cousin and companion, and a troubled, nearly suicidal drug user. The story Percy weaves around these and the extensive cast of minor characters is subtle and languid, existing only to propel us into the depths of human frailty. As to writing the other, Percy is a master, and this is the real lesson of the book for the striving writer. In Jack, the author gives us a protagonist who is utterly unsympathetic, save for his fastidiousness. Jack first describes himself this way:

I manage a small branch office of my uncle’s brokerage firm. My house is the basement apartment of a raised bungalow belonging to Mrs. Schexnaydre, the widow of a fireman. I am a model tenant and a model citizen and take pleasure in doing all that is expected of me…I subscribe to Consumer Reports and as a consequence I own a first-class television set, an all but silent air conditioner and a very long lasting deodorant. My armpits never stink. (pp. 6–7)All this from a man not yet thirty and in the prime of his life. But later we learn that tidiness and order, making money, and bedding his pretty young secretaries aren’t really enough for Jack: he is, it turns out, acutely aware that an anvil of superficiality is all that secures him, and a part of him wants to struggle against that. Learning this, we grieve with him at the death of his handicapped half-brother and share in his shame at the disapproval of his aunt.

Minor characters also move in and out, both to mirror Jack and to reinforce his manic view of the world. His description of Eddie Lovell, a friend he chats with on a street corner, tells not only of Jack’s extreme self-consciousness, but also of the avarice and emptiness that press in on him:

…As he talks, he slaps a folded newspaper against his pants leg and his eye watches me and at the same time sweeps the terrain behind me, taking note of the slightest movement. A green truck turns down Bourbon Street; the eye sizes it up, flags it down, demands credentials, waves it on. A businessman turns in at the Maison Blanche building; the eye knows him, even knows what he is up to. And all the while he talks very well. His lips move muscularly, molding words into pleasing shapes, marshalling arguments, and during the slight pauses are held poised, attractively everted in a Charles-Boyer pout—while a little web of saliva gathers in a corner like the clear oil of a good machine. (pp. 18–19)Similarly, Jack’s description of his Uncle Jules tells us more about Jack’s own shallow perspective than it does about his uncle and benefactor:

Uncle Jules is as pleasant a fellow as I know anywhere. Above his long Creole horseface is a crop of thick gray cut short as a college boy’s. His shirt encases his body in a way that pleases me. It fits him so well. My shirts always have something wrong with them; they are too tight in the collar or too loose around the waist. Uncle Jules’ collar fits his dark neck like a tape; his cuffs, folded like a napkin, just peep out past his coatsleeve, and his shirt front: the impulse comes over me at times to bury my nose in that snowy expanse of soft fine-spun cotton. Uncle Jules is the only man I know whose victory in the world is total and unqualified. (pp. 30–31)And then there are Walter Wade, who, briefly engaged to Kate, is a spotlight shining on Jack’s failures and shortcomings, and Mercer, the African American servant who unclothes Jack’s lingering racism.

And then, near the end of the book, when Jack is beginning to lose his cherished sense of control, there is the St. Louisan, a man he notices on the train during an ill-fated trip with Kate to Chicago. Jack observes this man in a physical way that suggests a feeling of arousal:

…His suit is good. He sits with his legs crossed, one well-clad haunch riding up like a ham, his top leg held out at an obtuse angle by the muscle of his calf.In time, as I’ll show later, this man from St. Louis casts a painful reflection that holds Jack captive, like the sight of an accident on the freeway.

His brown hair is youthful (he himself is thirty-eight or forty) and makes a cowlick in front. With the cowlick and the black eyeglasses he looks quite a bit like the actor Gary Merrill and has the same certified permission to occupy pleasant space with his pleasant self. (p. 188)

By presenting the story through memories, observations, and musings like these, Percy gently draws us into two competing dimensions of Jack’s worldview: the search and the malaise. He starts with the hopeful, the idea of a search that might deliver Jack from suffocating “everydayness.” Calling up his memory of being wounded in the war, Jack introduces the search to us this way:

…This morning, for the first time in years, there occurred to me the possibility of a search. I dreamed of the war, no, not quite dreamed but woke with the taste of it in my mouth, the queasy-quince taste of 1951 and the Orient. I remembered the first time the search occurred to me. I came to myself under a chindolea bush. Everything is upside-down for me, as I shall explain later. What are generally considered to be the best times are for me the worst times, and the worst of times was one of the best. My shoulder didn’t hurt but it was pressed hard against the ground as if somebody sat on me. Six inches from my nose a dung beetle was scratching around under the leaves. As I watched, there awoke in me an immense curiosity. I was onto something. I vowed that if I ever got out of this fix, I would pursue the search. Naturally, as soon as I recovered and got home, I forgot all about it. (p. 11)This mysterious idea of a search persists in his mind as he glides through his mundane morning preparations, until at last he addresses the reader directly and explains the search succinctly:

What is the nature of the search? you ask.At this point, the search is largely forgotten for 130 pages until Jack visits his mother’s house, where he and his secretary, Sharon, after whom he has long been lusting, visit his half-brothers and sisters, and where he is confronted by two perspectives on God: his and his family’s:

Really it is very simple, at least for a fellow like me; so simple that it is easily overlooked.

The search is what anyone would undertake if he were not sunk in the everydayness of his own life. This morning, for example, I felt as if I had come to myself on a strange island. And what does such a castaway do? Why, he pokes around the neighborhood and he doesn’t miss a trick.

To become aware of the possibility of the search is to be onto something. Not to be onto something is to be in despair. (p. 13)

My mother’s family think I have lost my faith and they pray for me to recover it. I don’t know what they’re talking about. Other people, so I have read, are pious as children and later become skeptical… Not I. My unbelief was invincibleIf the search is “to be onto something,” the malaise is the everydayness at constant war with it. The irony is that Jack is able to pursue the search with only the barest energy, but the malaise is something he feels deeply and viscerally. He first describes it, again directly addressing the reader, as he and Sharon drive to their initial outing at the beach:

from the beginning. I could never make head or tail of God…

…The best I can do is lie rigid as a stick under the cot, locked in a death grip of everydayness, sworn not to move a muscle until I advance another inch in my search. The swamp exhales beneath me and across the bayou a night bittern pumps away like a diesel. At last the iron grip releases and I pull my pants off the chair, fish out a notebook and scribble in the dark:

REMEMBER TOMORROW

Starting point for search:

It no longer avails to start with creatures and prove God.

Yet it is impossible to rule God out.

The only possible starting point: the strange fact of one’s own invincible apathy—that if the proofs were proved and God presented himself, nothing would be changed. Here is the strangest fact of all.

Abraham saw signs of God and believed. Now the only sign is that all the signs in the world make no difference. Is this God’s ironic revenge? But I am onto him. (pp. 145–146)

…As luck would have it, no sooner do we cross Bay St. Louis and reach the beach drive than we are involved in an accident. Fortunately it is not serious. When I say as luck would have it, I mean good luck. Yet how, you might wonder, can even a minor accident be considered good luck?Ultimately, even the search is fouled by experience, as Jack finds he is simply not up to it. It is the St. Louisan, the minor character more similar to Jack than any other, who brings this realization home to him on the train ride to Chicago with Kate:

Because it provides a means of winning out over the malaise, if one has the sense to take advantage of it.

What is the malaise? you ask. The malaise is the pain of loss. The world is lost to you, the world and the people in it, and there remains only you and the world and you no more able to be in the world than Banquo’s ghost.

You say it is a simple thing surely, all gain and no loss, to pick up a good-looking woman and head for the beach on the first fine day of the year. So say the newspaper poets. Well it is not such a simple thing and if you have ever done it, you know it isn’t—unless, of course, the woman happens to be your wife or some other everyday creature so familiar to you that she is as invisible as you yourself. Where there is a chance of gain, there is also chance of loss. Whenever one courts great happiness, one also risks malaise. (pp. 120–121)

…I have to admire the St. Louisan for his neat and well-ordered life, his gold pencil and his scissors-knife and his way of clipping articles on the convergence of the physical sciences and the social sciences; it comes over me that in the past few days my own life has gone to seed. I no longer eat and sleep regularly or write philosophical notes in my notebook and my fingernails are dirty. The search has spoiled the pleasure of my tidy and ingenious life in Gentilly. (p. 191)And when Jack reaches what should be a pinnacle, his chance to consummate his relationship with Kate, it is not the gallant search and its culmination that we experience, but rather the decisive victory of the malaise. By now, he has taken to voicing his remonstrations to the imagined person of Rory Calhoun, the actor, and all the romantic characters Rory has played. And to Rory and the many heroes he represents, Jack describes his fateful night with Kate:

I’ll have to tell you the truth, Rory, painful though it is. Nothing would please me more than to say that I had done one of two things: Either that I did what you do: tuck Debbie in your bed and, with a show of virtue so victorious as to be ferocious, grab pillow and blanket and take to the living room sofa… Or—do what a hero in a novel would do:… when it happens that a maid comes to his bed full of longing for him, he puts down his book in a good and cheerful spirit and gives her as merry a time as she could possibly wish for…As a story of failure and loneliness in a crowd, The Moviegoer, like Revolutionary Road, is not fanciful. It does not feel the need to revise history, fly or float off the planet, or create a new language. It simply gives us ordinary people who peel back the prosperity of the post-war era to expose the emotional barrenness underneath. On its journey into the depths of human lassitude, The Moviegoer takes the direct route.

No, Rory, I did neither. We did neither. We did very badly and almost did not do at all. Flesh poor flesh failed us. The burden was too great and flesh poor flesh, neither hallowed by sacrament nor despised by spirit (for despising is not the worst fate to overtake the flesh), but until this moment seen through and canceled, rendered null by the cold and fishy eye of the malaise—flesh poor flesh now at this moment summoned all at once to be all and everything, end all and be all, the last and only hope—quails and fails. (p. 199–200)

Note: Page numbers are from the First Vintage Internation Edition, April 1998, ISBN 0-375-70196-6.